Genesis

In his book, The Tree of Life, the great 16th century Kabbalist Isaac Luria (the Ari), founder of Lurianic Kabbalah, today’s predominant school of Kabbalah, wrote, “Know, that before the emanations were emanated and the creatures created, an Upper, Simple Light had filled the whole of reality. And there was no vacant place, such as an empty air and a void, but everything was filled with that simple, boundless Light.” [42]

Since then, only one Kabbalist has ventured to compose a comprehensive explanation of these profound phrases, as well as introduced a complete commentary on The Book of Zohar: Kabbalist Rav Yehuda Ashlag, Baal HaSulam. In his six-volume commentary on the writings of the Ari, known as Talmud Eser Sefirot (The Study of the Ten Sefirot), Baal HaSulam explains that the Light that the Ari refers to is “All the pleasant sensations and conceptions in the world.” [43] He also defines “Light” as “everything but the substance of the vessels [desire to receive].” [44]

In other words, there are only two “beings” in existence: the desire to bestow, to give, which Ashlag defines as “light,” “Creator,” or “pleasure,” and the desire to receive pleasure, to enjoy, which he calls “a vessel,” “the creature,” or “the created being.” To understand how the whole of reality can emerge from only two desires, we need to take a deeper look at how they interact.

Four Stages and the Root of Creation

Electricity, gravity, and all of Nature’s other forces are timeless phenomena. In other words, you cannot point to a specific point in time at which they were created because Nature’s forces are not particular events; they are potentials or fields that cover the whole of space-time. They manifest under certain conditions and, given the right instruments, we can detect their existence.

To prove the existence of electricity, you need a resistor of some sort, like a lamp or a current-meter. Without something that resists the flow of the electric current, we could never know that electricity was flowing through it, and we could never discover the existence of electricity. Similarly, to prove the existence of gravity, we need to observe its effect on physical masses, and to discover light, we need an object that the light illuminates, meaning stops the light and reflects it back to our eyes.

In precisely the same way, Kabbalists discovered the desire to bestow through that desire’s interaction with its resistor—their own desires to receive. When they refined and calibrated their resistors—desires to receive—they were able to detect the force that operated those desires. That was how Abraham discovered that the force that operated his desires and the rest of reality was a desire to bestow. This is the knowledge that Abraham passed on to his sons and students, and this is still the knowledge that Kabbalists pass on from teacher to student, and now to the entire world.

As a side note, the difference between one Kabbalist and another is not in the knowledge each conveys, but in the language and style each uses to convey it. The reason I am relying mostly on Ashlag’s writings is not that he had more extensive knowledge than, say, the Ari. I am using his writings simply because he was the most recent Kabbalist, and wrote in the most contemporary style. Therefore, he is the easiest to understand for a 21st century reader with little or no background in Kabbalah. The farther we go back in time, the harder it is to grasp the full meaning of Kabbalistic texts.

Returning to the discussion at hand, in his The Study of the Ten Sefirot, Ashlag tells us that this desire to bestow created the desire to receive as a necessary offshoot of its wish to bestow [45]. In other words, because the desire is a desire to give, it created something that wishes to receive. Thus, just as it is impossible to explain what is a day without also understanding what is a night, or to understand the concept of “left side” without having the concept of “right side” either, it is impossible to perceive the desire to receive without perceiving the desire to give.

To put matters in the right context, when Kabbalists speak of the Creator, they are referring to the desire to give, and when they speak of Creation, they are referring to the desire to receive the Creator’s giving. Also, when they are presenting a dialog between the Creator and the creatures, such as we find in the Bible, they are actually introducing a specific interaction between the desire to give and the desire to receive, not an exchange of vocalisms between a protein aggregate and a voice in the clouds.

In that regard, at the conclusion of his introduction to The Study of the Ten Sefirot (Item 156), Ashlag takes special care to warn us: “Yet, there is a strict condition during the engagement in this wisdom—to not materialize the matters with imaginary and corporeal issues. This is because thus they breach, ‘Thou shall not make unto thee a graven image, nor any manner of likeness.’ … To rescue the readers from any materialization, I composed the book, The Study of the Ten Sefirot by the Ari, where I collect from the books of the Ari all the principal essays concerning the explanation of the ten Sefirot in as simple and easy language as I could.” [46]

Thus, at the basis of existence lies not matter, but forms of desire to receive pleasure created by interactions with their Creator—the desire to give pleasure.

To tie this approach to more familiar territory, think of lightning. To the ancient Greeks, the thunderbolt was Zeus’ traditional weapon. To us, the exact same thunderbolt is merely “The visible discharge of electricity that occurs when a region of a cloud acquires an excess electrical charge that is sufficient to break down the resistance of air,” if we consult the Encyclopedia Britannica [47].

Similarly, understanding the true meaning of Abraham's story requires an explanation by one who has acquired sufficient knowledge to explain it in a matter-of-fact, rational manner, meaning a Kabbalist, and preferably one of substantial understanding and sufficient didactic skills, such as Ashlag.

Going After the Thought of Creation

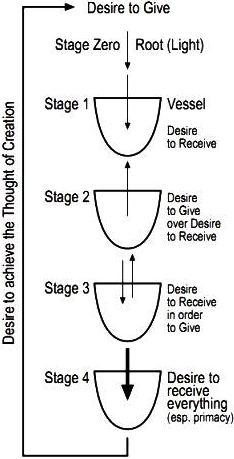

In “Preface to the Wisdom of Kabbalah,” [48] Baal HaSulam divides the onset of Creation into five stages and one restriction, but we can cluster them into three groups. Think of the first two groups as a car and the fuel for its engine, and imagine that the third group is the driver.

The first group contains only Stage Zero, the Root. This is the desire to give, the energy that creates and sustains the car called “Creation” (it’s a very old model; they don’t make them like that anymore).

The second group—Stages One and Two—builds a “platform” for evolution. This is the car itself. In a sense, the platform that the two stages have built resembles what Richard Dawkins described in The Selfish Gene as “The primeval soup," [49] the oceanic substrate that contained the ingredients for life’s inception.

The third group—Stages Three and Four—is “the driver.” Its role is to start the engine of evolution—the interaction between the desires. As we will explain below and in the next chapter, the restriction is the wheel with which creation is driven toward its purpose: discovering the Thought of Creation.

Stages Zero and One

First, a general comment about the stages: Since Kabbalah has gained popularity in recent years, some of its terms have surfaced in various connections. The term Sefirot is often mentioned in relation to the origin of Creation. It is possible to describe the process of creation using the names of Sefirot instead of stages, but this might complicate matters needlessly. To see how the Sefirot and the four stages relate to the same process, refer to the essay, “Preface to the Wisdom of Kabbalah.” [50]

In Kabbalistic terms, the existence of a desire to bestow without a desire to receive is called “the Root Stage” or “Stage Zero.” The Root Stage is immediately followed by its mandatory offshoot—“Stage One”—the desire to receive, which is permeated with the abundance given to it by the Root, the desire to bestow.

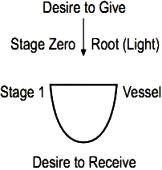

As a result, no element in existence, from subatomic particles to the most expansive galaxies in the universe, escapes the giving-receiving “bipartisanship.” It may appear in the form of hot vs. cold, dry vs. wet, small vs. big, centrifugal vs. centripetal, energy vs. matter, etc., but they all stem from the primordial opposites: giving and receiving. To portray this interaction, I use a downward arrow to denote the desire to give, and a bowl or receptacle (usually referred to as a “vessel”) to denote the desire to receive (Figure no. 1).

Figure no. 1: The Root Stage is immediately followed by its mandatory offshoot—“Stage One”—which is the desire to receive, permeated with the abundance given to it by the desire to bestow.

The Root is known as “light” and the desire to receive, as “vessel.”

Stage Two

The result of the meeting between the two desires in Stage One is Stage Two. Here is where the actual interaction between the desires truly begins. To understand the shift that occurs between Stage One and Stage Two, consider a child’s admiration for its parents. Because children, especially in early childhood, idolize their parents, they strive to imitate them. They closely observe their parents’ every move (with a tendency for boys to observe their fathers and for girls to observe their mothers), “study” their parents’ demeanor, and try to follow suit.

Contemporary studies show how attentive children are to their parents’ guidance. In Perspectives on Imitation: From Neuroscience to Social Science, Dr. Andrew Meltzoff and Prof. Wolfgang Prinz of Cambridge University, UK, write, “ Parents provide their young with an apprenticeship in how to act as a member of their particular culture long before verbal instruction is possible. A wide range of behaviors—from tool use to social customs—are passed from one generation to another through imitative learning.” [51]

Also, Dr Benjamin Spock’s Baby and Child Care bestseller on parenting provides such a complete description of this process that I feel compelled to present it here in full: “Identification is a lot more important than just playing. It’s how character is built. It depends more on what children perceive in their parents and model themselves after than on what the parents try to teach them in words. This is how children’s basic ideals and attitudes are laid down—toward work, toward people, toward themselves ... This is how they learn to be the kind of parents they’re going to turn out to be twenty years later, as you can tell from listening to the affectionate or scolding way they care for their dolls.

“Gender awareness. It’s at this age that a girl becomes more aware that she’s female and will grow up to be a woman. So she watches her mother with special attentiveness and tends to mold herself in her mother’s image: how her mother feels about her husband and the male sex in general, about women, about girl and boy children, toward work and house work. The little girl will not become an exact copy of her mother, but she will surely be influenced by her in many respects.

“A boy at this age realizes that he is on the way to becoming a man, and he therefore attempts to pattern himself predominately after his father: how his father feels toward his wife and the female sex generally, toward other men, toward his boy and girl children, toward outside work and housework.” [52]

And just as a child wishes to grow up to be like its parent, Stage Two in the evolution of the desire is an expression of the wish of the desire to receive (Stage One) to be like its parent—the desire to give (the Root). This happens because as it is a desire to receive—the “offspring” of the desire to give—Stage One recognizes the Root’s superiority and wishes to be like its progenitor. And because the only example that Stage One receives from the Root is that of giving, in Stage Two the desire to receive begins to want to give, as well.

Earlier, we said that at the basis of existence are forms of the desire to receive, created by interactions with their creator—the desire to give. Thus, through two natural, “automatic” reactions to giving, two opposite desires emerge: to receive (in Stage One), and to give (in Stage Two). The various combinations of these two desires form the basis of every object, every event, and every evolution that occurs in our world, including us—our bodies, our thoughts, and our actions.

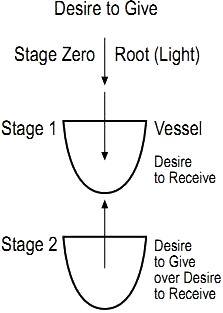

Just as a child wishes to become like its role-model parent, at the root of the desire to give in Stage Two lies the desire to receive its progenitor’s superior status, power, and knowledge. In other words, Stage Two is a desire to receive the status and nature of giving. For this reason, it is best to picture Stage Two as a vessel (desire to receive) that wishes to give, or “vessel of bestowal.” Hence, the arrow designating this desire points outwards, toward the Creator (Figure no. 2).

Figure no. 2: At the root of the desire to give in Stage Two lies the desire to receive. Therefore, it is best to picture Stage Two as a vessel (desire to receive) that wishes to give, or “vessel of bestowal.”

But Stage Two is more than just a new desire. In wanting to give, Stage Two is admitted into an entirely new state of being. Because it no longer wishes to receive, but to bestow, it must have someone upon whom to bestow. Thus, to be like its creator—a giver—Stage Two must act positively and favorably toward others.

For this reason, Stage Two, the force that compels us to give despite our underlying desire to receive, is the force that makes life possible. Without it, parents would not have children (to whom they can bestow) or care for their offspring once they are born, life would not be possible.

Indeed, the best example of Stage Two is a mother’s love for her child. If we consider the endless love, compassion, and effort mothers put into raising their babies, we are left in awe and admiration that such devotion is even possible. Yet, when you look at a mother’s face while she is nursing, changing diapers, or bathing her baby, often you will find that she is glowing. Why is this so? What gives mothers the ability to not only endure such strain, but to wish for it and enjoy it?

The answer is simple, and every mother knows it instinctively: In giving to their babies, they experience tremendous joy. There is a desire to receive the pleasure of motherhood (or parenthood) behind every decision to bring a new life into the world. Without it, people would not have babies, unless by mistake, and this would be very unfortunate for the children.

Now we can see why Nature’s initiating force is the desire to give, and not the desire to receive. Concisely capturing the essence of that concept is Baal HaSulam’s Kabbalistic definition of altruism. In 1940, he published a paper titled, “The Nation.” In it he writes, “The altruistic force [the desire to give] is like centrifugal waves—an outward aiming force… which flows from within outwardly.” [53]

Stage Three

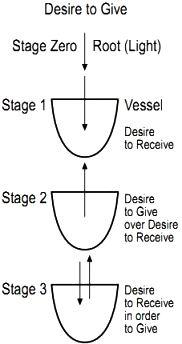

As Ashlag stated, the evolution of desires, which hang down by cause and effect, is mandatory, adhering to fixed, determined rules. The next mandatory step is for Stage Two to start giving, since this is what it wants to do. But in Stage Two the newly made desire to give has a problem to solve: it wishes to give, but all that exists besides itself (the desire to receive with its two stages) is the desire to give that created it. Therefore, the only thing that Stage Two can give to its creator is its willingness to receive. In other words, it will receive, just as in Stage One, but with the intention to give pleasure to the Root—the Creator. This “inverted” modus operandi, where the act is reception but the intention is to give, is a completely new concept and hence merits a new name—“Stage Three” (Figure no. 3).

It may seem awkward to some, but we apply this mode of action routinely in our relationships. Think of a young man who comes to visit his mother after not having seeing her for a long time. It is quite likely that his mother will want to prepare something to eat for her darling son. But what if the son is not very hungry? Will he not eat? In most cases, he will eat and express his delight at the food simply because it pleases his mother.

Figure no. 3: In Stage Three, the desire to receive chooses to receive not because it enjoys it, but because this is what pleases the Root, the desire to give.

In this case, the son is not focused on his own pleasure, but on his mother’s pleasure in watching him eat. In “Preface to the Wisdom of Kabbalah,” [54] Baal HaSulam describes this mode of work as partial use of the desire to receive, just the necessary minimum for the reception of pleasure, while maintaining the center of attention on the giver’s delight at the receiver’s acceptance. In our culinary example, the son must have some appetite or he will not be able to eat at all. However, his appetite should not be big enough to shift his intention (or attention) from pleasing his mother to pleasing himself.

Stage Four

When the son’s appetite is mild enough to be subordinate to his desire to please his mother, he can focus on his intention to please, rather than on his stomach. But what if he were very hungry and had not eaten for a whole day? Would he still be able to ignore his rumbling stomach, focus only on his mother’s pleasure, and eat only because it pleases her? When Stage Three begins to receive because it wishes to please the Root, it realizes that the more it receives, the more it pleases its maker, the Root.

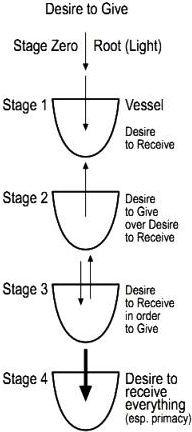

In consequence, it begins to wish to receive more and more and more. Finally, it wishes to receive everything, just as in Stage One, thus reawakening the whole of its desire to receive. This self-evoked total desire to receive is called “Stage Four.”

Yet, there is a fundamental difference between Stage One and Stage Four: relation to the giver. Stage One does not relate to the giver, only of the abundance. As soon as it “realizes” there is the desire to give that created it, it wishes to be like the giver, and this initiates Stage Two. Stage Four is realizes not only the giver’s existence, but also of the giver’s benevolence and primacy, since it is the desire to give that initiated creation. And being a complete desire to receive, Stage Four wishes to receive not just the abundance that Stage One receives, but the primacy status of the Root (Figure no. 4).

Figure no. 4: Being a total desire to receive, Stage Four wishes to receive not just the abundance that Stage One receives, but the primacy status of the Root.

However, to receive such a status, Stage Four must be Creator-like, and it is not. Instead, it is a conscious desire to receive everything—omnipotence, omniscience, and even the nature of the Creator. Anything less than that would be incomplete, since it would not be precisely identical to the Creator. This is what Ashlag means when he writes in “Preface to the Wisdom of Kabbalah” [55] that Stage Four wishes to achieve the Thought of Creation (Figure no. 5).

Figure no. 5: Stage Four wishes to achieve the Thought of Creation

In another essay, “The Giving of the Torah [Light],” Ashlag offers a beautiful explanation of the nature of the Creator-created relationship that occurs at the outset of Creation: “This matter is like a rich man who took a man from the market and showered him with gold, silver, and all desirables each day. And each day he gave him more gifts than the day before. Finally, the rich man asked, ‘Do tell me, have all your wishes been fulfilled?’ He [the man] replied, ‘Not all of my wishes have been fulfilled, for how good and how pleasant it would be if all those possessions and precious things came to me through my own work, as they have come to you. Then I would not be receiving the charity of your hand.’ Then the rich man told him, ‘In this case, there has never been born a person who could fulfill your wishes.’” [56]

This resentment of gifts was well observed in research conducted by Amani El-Alayli and Lawrence A. Messe of Michigan State University. Their findings, published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, were that when receiving unexpected favors, people may experience two opposing emotions: a desire to reciprocate the favor, which the researchers correctly described as “obligation,” or resentment, which they referred to as “psychological reactance.” [57]

Moreover, they wrote, “Participants’ evaluations of the supervisor [benefactor] suggested that people have mixed impressions of someone whose favors violate [exceed] expectancies or norms.” [58] This research clearly demonstrates that it is a natural human trait to feel shame and embarrassment when treated with exceptional generosity. These emotions, Kabbalah explains, are directly rooted in the shame that Stage Four experiences when faced with unbounded giving without the chance of becoming a giver, too.

Thus, when Stage Four realizes it cannot obtain the Root’s primacy, it realizes that it cannot receive everything and that it is inherently inferior to its maker. This instantly extinguishes any sensation of pleasure in Stage Four, and despite the infinite abundance that the Root gives, Stage Four remains with a sense of emptiness, since its biggest wish has not been granted. In Kabbalah, when Stage Four’s desire to be like its maker overshadows all other pleasures, it is called “restriction.” Because the desire to be like the Creator is so much greater than all other desires, it practically prevents pleasure from being experienced.

From here on, evolution will unfold in a single underlying purpose: to repossess that great abundance that the Root wishes to give, and which can be received only with the intention to bestow.

[42] Isaac Luria (ARI), Tree of Life, Gate 1, Branch 2

[43] Yehuda Ashlag, Talmud Eser Sefirot (The Study of the Ten Sefirot), Part 1 (Israel: Ashlag Research Institute, 2007), 19

[44] Yehuda Ashlag, Talmud Eser Sefirot(The Study of the Ten Sefirot), Part 1 (Israel: Ashlag Research Institute, 2007), 31

[45] Yehuda Ashlag, “Talmud Eser Sefirot (The Study of the Ten Sefirot), Part One, Histaklut Pnimit (Inner Reflection),” in Kabbalah for the Student, trans. Chaim Ratz (Canada: Laitman Kabbalah Publishers, 2009), 729

[46] Yehuda Ashlag, “Introduction to Study of the Ten Sefirot,” in Kabbalah for the Student, trans. Chaim Ratz (Canada: Laitman Kabbalah Publishers, 2009), 374

[47] “Lightning,” Encyclopedia Britannica (http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/340767/lightning)

[48] Ashlag, “Preface to the Wisdom of Kabbalah,” in Kabbalah for the Student, 567-572

[49] Richard Dawkins, The Selfish Gene (New York: Oxford University Press Inc., 1989), 14

[50] Ashlag, “Preface to the Wisdom of Kabbalah,” in Kabbalah for the Student, 567-9

[51] From: S. Hurley and N. Chater (Eds.), Perspectives on Imitation: From Neuroscience to Social Science (Vol. 2) (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), 55-77

[52] Benjamin Spock, Baby and Child Care, (USA: Pocket Books, 2004), 164-5

[53] Ashlag, Kitvey Baal HaSulam(The Writings of Baal HaSulam) (Israel: Ashlag Research Institute, 2009), 499

[54] Ashlag, “Preface to the Wisdom of Kabbalah,” in Kabbalah for the Student, 568

[55] Ashlag, “Preface to the Wisdom of Kabbalah,” in Kabbalah for the Student, 568

[56] Yehuda Ashlag, “The Giving of the Torah,” in Kabbalah for the Student, 244

[57] El-Alayli Amani and Lawrence A. Messe. “Reactions Toward an Unexpected or Counternormative Favor-Giver: does it matter if we think we can reciprocate?” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 40.5 (September 2004): 633-641

[58] (ibid.)